The Internet is flooded with negative reviews of Warner Bros. Suicide Squad movie. Is it a reaction to a poor movie, or simply a reaction to a greater cinematic theme that audiences won’t recognize for several years?

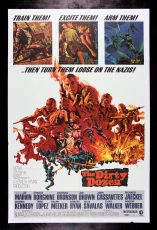

THE DIRTY DOZEN

I went to see Suicide Squad last night, and while it isn’t a perfect movie, it is still a good movie. Reviews on the Internet and other places are not so kind, calling the movie a dark, soulless slog through the streets of Midway City, and others pointing out the premise of villains fighting for the government as so absurd that the movie should be dismissed outright. There are certainly some valid critiques among the thousands of reviews that have been released, but it got me wondering what critics thought of the 1967 “classic” The Dirty Dozen with Lee Marvin.

In Bosley Crowther’s 1967 New York Times review, the critic said,

In Bosley Crowther’s 1967 New York Times review, the critic said,

“It is not simply that this violent picture of an American military venture is based on a fictional supposition that is silly and irresponsible. Its thesis that a dozen military prisoners, condemned to death or long prison terms for murder, rape, and other crimes, would be hauled out of prison and secretly trained for a critical commando raid behind the German lines prior to D-Day might be acceptable as a frankly romantic supposition, if other factors were fairly plausible.

But to have this bunch of felons a totally incorrigible lot, some of them psychopathic, and to try to make us believe that they would be committed by any American general to carry out an exceedingly important raid that a regular commando group could do with equal efficiency—and certainly with greater dependability—is downright preposterous.

And then to bathe these rascals in a specious heroic light—to make their hoodlum bravado and defiance of discipline, and their nasty kind of gutter solidarity, seem exhilarating and admirable—is encouraging a spirit of hooliganism that is brazenly antisocial, to say the least.”

It’s interesting that you can take out any reference to military and World War II in the above paragraphs, and you could easily mistake it for a Suicide Squad review written this week.

Roger Ebert, in his first year as a reviewer for the Chicago Sun-Times, spent his column space criticizing the burning of human bodies in The Dirty Dozen as a form of entertainment, while censor boards instead put greater emphasis on covering the nude body. There is certainly a lot of violence in Suicide Squad, but because the human inhabitants of Midway City have been transformed into unworldly beasts, the constant beheadings and deaths on screen, managed to keep the movie to a PG-13 rating.

THE FILM SCHOOL GENERATION

By the end of 1967, public approval for the Vietnam War started to wane. Though the 1968 Tet Offensive was a success for the U.S. military, it also had the negative consequence of driving support for General Westmoreland to an all-time low, and is noted as one of the main reasons Lyndon B. Johnson did not run for re-election. The media certainly played a role in public perception and realities of war, as coverage of the war became increasingly negative. Images of civilian and military casualties were televised, and the ugliness of war became a bigger focus, resulting in the types of movies audiences would see in the coming years.

While there were a number of movies prior to 1965 that gave audiences a “real” look at war, the number of “war is hell” movies increased after The Dirty Dozen. Instead of just seeing war, with John Wayne leading troops to victory, audiences were able to see that war comes with a price in movies like The Green Berets (1968), Go Tell the Spartans (1979), and Platoon (1987).

Soldiers returning from the Vietnam War expecting a hero’s welcome, were instead met with hatred, unemployment, and post-traumatic stress disorder. Unrest in America was at an all-time high, and certainly it was most apparent at colleges and universities, where anti-war sentiment and free thinking had become the norm. Coincidentally, through the ‘60s and ‘70s, film and television majors grew to an all-time high. The number of students pursing degrees in film and television was up to 44,000 by 1980, and each of those students were exposed to the general malaise and anti-establishment thinking coursing through the country. This group was also exposed to world cinema unlike generations before them. French New Wave, Asian cinema, Auteur Theory and a reintroduction to classics had to be a culture clash on conventional thinking like none have seen before or since.

Those who graduated from their respective programs followed the trend of the television generation that was routinely breaking from convention (i.e. war coverage), and set out to tell stories in their own way. The Film School Generation graduated Martin Scorsese, George Lucas, Steven Spielberg, Brian DePalma, and John Milius, who all looked up to the earliest graduates of the new way of storytelling; Francis Ford Coppola, Sam Pekinpah, and Akira Kurosawa. Instead of making films for general audiences, the Film School Generation began making films for their peers—other young movie lovers of the ‘70s.

Initially, these filmmakers were not interested in making commercial hits, they were interested in analyzing film, and creating new works that were a reflection of the times. What we got was a collection of films that are still celebrated today. The Wild Bunch, The Godfather, The Conversation, Taxi Driver, Mean Streets, Raging Bull, Jaws, Dog Day Afternoon, One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest, Straw Dogs, and Bonnie and Clyde, were lauded for their “realistic” take on the human condition, but also were chastised for their dark tones, intense sexual situations, and the perceived glorification of violence and the anti-hero.

A REFLECTION OF THE TIMES

As it turns out, the movies of the late ‘60s, ‘70s, and early ‘80s were simply the filmmakers holding a mirror to society—intentionally or unintentionally. The images of dead soldiers and civilians flickering on their television, a faltering economy, the impeachment of Richard Nixon, had to have been subconscious influences on these filmmakers who then told tales that mirrored the zeitgeist of the American public.

The Me Generation and corporate greed (this includes the conglomeration of media), certainly brought forth the family-friendly and raunchy comedy flicks that permeated theaters through the ‘80s and ‘90s, but interestingly, other, smaller trends have been noted by film critics and scholars over the years. For example, David Mooney states scary movies succeed in recession “because they reflect what is scaring us now.”

Economic horror or horror that reflects the mood of a nation is a factor also. Indeed, the most iconic of the Universal monster movies were all produced during the Great Depression, with films including Dracula, Frankenstein and King Kong emerging as things were getting bad. The next generation of horror came about during the 1970s, with The Texas Chainsaw Massacre arriving in 1974—smack bang in the middle of the 1973-75 recession.

Authors like King and John Kenneth Muir point to 1970s films like The Amityville Horror as being anchored in a sense of economic horror, reflecting the concern and fear felt by many families at the time. “In terms of the times—18 percent inflation, mortgage rates out of sight, gasoline selling at a cool dollar forty a gallon—The Amityville Horror, like The Exorcist, could not have come at a more opportune moment,” King argues.

We also live at a time where social issues are at an all-time high as the country (and world) are continually in conflict over topics that were, in the past, swept under the carpet, ignored, or actively put down by those in control. Is it any surprise then that movies set in a dystopian future are on the rise?

Which brings us back to Suicide Squad.

While many will point to Man of Steel, Batman v Superman, and Suicide Squad as dark and disturbing takes on the superhero genre, the Marvel Cinematic Universe has also made a slow move to darker themes in movies like Captain America: The Winter Soldier, Avengers: Age of Ultron, and Captain America: Civil War. Even the most recent Star Wars was a dark film, with somber underpinnings, and themes.

Perhaps our attention to the darker themes and violence are more noticeable because these movies are designed first and foremost to be blockbusters by the studio. If that is the case, will we look back in a decade and see that these movies were the filmmaker’s attempt to reflect societal concerns and themes, instead of just being dark for dark’s sake? If The Dirty Dozen was an indication that war movies were taking a turn away from expectations, and a new era of storytelling was occurring that held a large mirror to society, I think the same will be said of the Suicide Squad in ten years.

In the ’80s, The Dark Knight Returns ushered in a new take on the superhero. it was dark, it was rough, it was a reflection and commentary on the corruption of government and ideals that heroes originated. The tome was hailed at the time as a great work, and because of its success, nearly every superhero has become dark and brooding. That is until those expectations changed. The Flash television series on The CW introduced a hero that, despite living in a dark world, is optimistic, who is always looking for hope. Supergirl is the same way, and when the two come together on the small screen, it’s magic.

HINDSIGHT IS ALWAYS 20/20

Right now, the Suicide Squad is the third movie in the DC Comics Extended Universe that seems to be dark and brooding, and it is definitely a turn off for many. While the general public may not be able to see it now, I think Suicide Squad is the film that indicates filmmakers are struggling to address their shock, anger, despair, and frustration of the country’s divide on every major social issue confronting citizens on every news channel and Internet site.

So, while we may not like what is happening to our favorite heroes on the big screen, there were those who did not like what filmmakers were doing with the movie idols in the ‘60s and ‘70s either. It’s really no wonder audiences are surprised this isn’t a “fun” movie. In a decade we’ll see the Suicide Squad was right on target in reflecting the mood of society; dark and without a lot of humor — where, like The Dirty Dozen, our heroes are villains, and our lack of compassion for our fellow citizens make it easy to kill and maim in the name of entertainment.

8 Comments

Stephen, this is a fantastic article and one of the best I’ve read on the site. You make some great points and the similarities between Suicide Squad and Dirty Dozen are uncanny. I liked Suicide Squad even though I thought the second half turned into the Will Smith show. It very well may be a reflection of the times. I know this movie would never have been made in the 90’s or even early 2000’s. It will be interesting to see how time changes these movies.

Thank you. Hopefully there will be more like this on a regular basis going forward.

Great article! I’m honestly very surprised if anyone is not expecting similarities between Dirty Dozen and Suicide Squad, because they are essentially exact same thing and its not a coincidence. While Seven Samurai is far more appealing take on “group of people against impossible odds” idea, not to mention a far superior film, not everything needs to nice and happy. Seven Samurai was very sad and realistic film, just not gratuitously violent.

I think the problem is what critics and general audience expects super hero genre to be like: They saw Christopher Reeve Superman and silver age goofy Superman books, they saw ’66 Batman series. What they didn’t see was The Dark Knight Returns or Watchmen. Only creators who make these comics and movies read them, film critics and average movie goers never heard of them. They don’t know when and why superheroes changed, they don’t see references and they don’t care. They want what they remember Superman and Batman being like back in the day, not even necessarily what they actually were like. Marvel does their movie heroes like they were before 90’s, DC does the same with their TV shows, for the most part. Those are well liked because they are easy to digest by the fans of the comics and general audience, they are what people expect.

I don’t think its even a quality of these gritty DC movies. While they are far from masterpieces, its the tone and style that’s too different for casual viewer. I got an example: When Netflix Daredevil came out, it was amazing: I love it, critics loved it, websites I go loved it. When I told couple of my friends, casual super hero fans, not comic reading type but much more knowledgeable about the genre and characters than average person about it and asked later what they thought, I was almost shocked: Responses varied from “it was alright” to “meh”. Later, I was thinking “How can this be, its excellent?” and then I realized its the same thing as current DC films: It was not what they expected, it was gritty, it was full of references they didn’t notice, they never read Miller’s Daredevil. They expected acrobatic bouncy guy and fast paced action, it was not that at all.

I also agree that entertainment goes with the times. Here, in Finland, there’s always a big bump in comedies when there’s economic depression.

All that said, even I am not a big fan of this gritty style in general, only with characters like Daredevil and Punisher, for example. I would say that there is a time and place for everything.

This was a great article,but I think you are being too generous to Suicide Squad with your comparison. This movie is getting bad review because it fails to deliver its message in a meaningful way. It portrays a government trying to weaponize meta humans, which turns out to be a bad idea, but then turns or to be a good idea after all. It also has a weird redemption theme that it tries to squash then lets happen so that it can be squashed again.

Just saying. My son ,who’s 10, loved the movie more than anything in the world.

And I think the movie was great! It was by far the best DC movie since the Nolan Batman.

You just need to know what you are getting into.

You don’t go to a pizzeria and complain over not getting a big steak and a great salat.

This is exactly the point I was making. Adults and critics have different expectations to kids. Casual viewers have different to hardcore comic fans and people who have seen 1000+ movies over several decades have different to people who only saw few dozen.

I liked it better than Xmen (all of them) but I still hate this darkness crap. Superman daylight, everything else Dark Knight. That trend needs to die, Right Now.

I actually thought SUICIDE SQUAD would be better received critically but I’m not surprised or broken up that it wasn’t because I’m one of the few who cares to say I have no problem with the stylistic or tonal choices the DCEU has taken so far. I like my four-color idols to be taken in new directions on the page and the screen because I grew up with the Reeve Superman and while I’ll always love that version I’m not trying to see it rehashed on the screen again. Superheroes, corporate superheroes especially, don’t have to be done one way and they are durable enough to touch on contemporary issues like terrorism, government overreach, and the prison-industrial complex as SQUAD does even obliquely. I take to that like a dog to a bone because superheroes and villains should not be timeless but of the times to stay relevant into the future.